Before I joined TechCongress as a communications intern in the fall of 2025, I was a security engineer trying to reconcile my past in civil service with my future in commercial technology. I often wondered whether these two worlds were destined to collide or whether I would eventually have to choose between them. I had built an early career in public policy across the executive and judicial branches, and spent years researching and educating on cybersecurity and AI policy through a number of non-profit organizations. It was not until I encountered TechCongress, a community of technology policy professionals combining their technical expertise with research and legislative work, that I realized I could do the same by simply pursuing both.

As I considered a future pivot into tech policy, a series of questions surfaced. What does the work actually look like? How should someone prepare? To find answers, I spoke with many seasoned practitioners, including Hill staffers, think tank researchers, and non-profit communicators and operators. What had once been an abstract landscape slowly transformed into a vibrant and thriving community with its own norms, nuances, and intellectual culture.

From my time with TechCongress, I have assembled a set of observations, some intuitive and others less obvious, that I wish I had known earlier. I offer them here for early career engineers and technologists who want to understand not only the work of tech policy, but more importantly, the unspoken habits and expectations that define this field.

Find your niche policy area, and commit to it.

One of the earliest and most consequential decisions you will make is identifying a policy domain narrow enough to be actionable yet broad enough to sustain long-term relevance. Areas like artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, critical infrastructure, and biotechnology each contain their own subfields and debates, and it can feel overwhelming to locate a starting point. Rather than attempting to master everything at once, select a niche based on your intellectual interests, prior experience, and the specific problems you feel compelled to address. Then commit to learning it well. Hill offices, think tanks, agencies, and non-profits rely on subject-matter experts who can contextualize breaking developments, translate technical ideas into accessible language, or frame certain issues. Over time, your niche can become a point of reference that guides your reading and projects, as well as where you can contribute. Focusing on a policy domain early on won’t limit you but rather establishes the base from which additional areas of expertise can be integrated thoughtfully.

R Street Institute’s panel, “Modernizing Federal IT Systems: Is Government Ready for AI?”, was one of the first Capitol Hill events I attended during my internship. Panels like this offer a valuable way to hear directly from experts, follow emerging debates, and deepen your understanding of a policy area.

Reading and writing will define your career. Embrace them early.

Once you identify your niche, your day-to-day life will revolve around consuming information and producing analysis. Technology policy moves through a constant stream of publications and reports, hearings, academic studies, and industry perspectives. Treat reading as a steady practice rather than an occasional task, and carve out time each week to keep up with the latest material. Equally as important is writing early and often on tech policy issues. I learned quickly that waiting for the “perfect moment” to start writing is a trap. Early memos and drafts of your thoughts may feel rough or incomplete, but the exercise of writing itself will accelerate your learning and communication skills. The more you write, the more fluent you will become in the language of your field: the concepts, the debates, and the subtle turns of jargon that show genuine interest and familiarity.

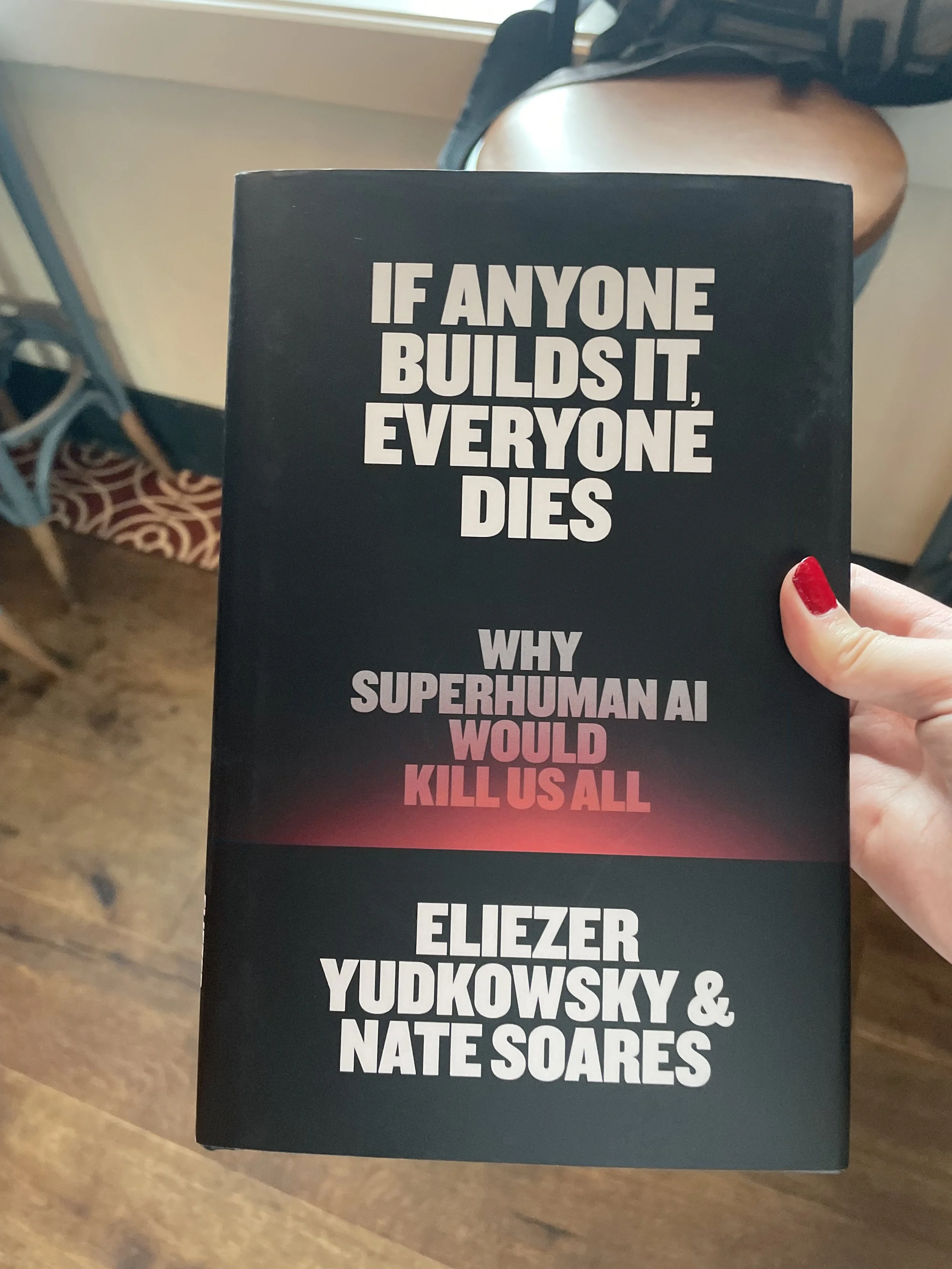

Book launches are an integral part of the tech policy world, often convening high-profile researchers, practitioners, and community members. Here, I attended Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares’ highly anticipated book at the Junction Bistro & Bar, hosted by the Machine Intelligence Research Institute.

Seek out the people and resources that move you toward your goals.

Policy careers are built on relationships. The more your network expands, the more your opportunities will, too. Tech policy can seem intimidating from the outside, but almost everyone I reached out to was happy to chat, share their experiences, or point me to helpful resources, so take advantage of the learning culture D.C. promotes. Don’t be afraid to reach across political lines either; some of the most insightful conversations I had were with people whose backgrounds were very different from mine.

I also discovered how useful online spaces can be. Substacks, X threads, policy podcasts, and research newsletters are all great ways to stay plugged in and learn from people who think deeply about these issues. Above all, try to tune out the imposter syndrome, although the learning curve may seem daunting and insurmountable. Everyone starts from somewhere and builds from the ground up. What matters is being curious, asking questions, and surrounding yourself with people who push you a little further each time. The relationships you invest in will open doors for you just as much as the content you study.

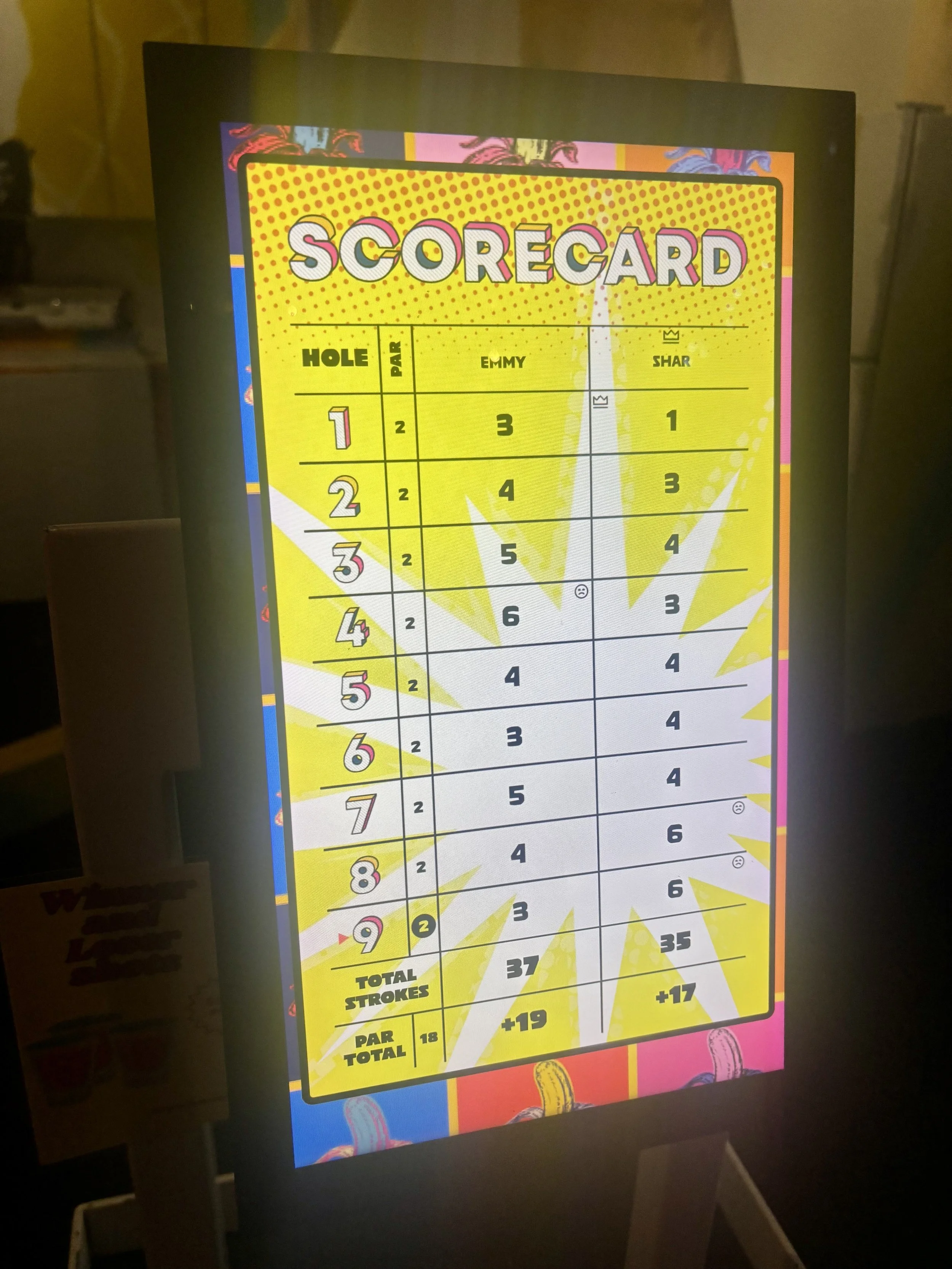

The 2025 TechCongress cohort wrapped up their fellowship with an End of Fellowship celebration at Puttery, a mini-golf venue and bar. Sharanya Maddukuri, the Fall 2025 Programs Intern, and I also joined them in marking the conclusion of our internships.

Tech policy depends on engineers, analysts, communicators, and researchers who can translate complex ideas into decisions that serve the public interest. In short, tech policy needs YOU.

I am deeply grateful to TechCongress for giving me a platform and illustrating these ideas to me over the course of my internship. By upskilling technical expertise in Congress and advancing a government that works for the people, TechCongress is an outstanding example of the kind of service aspiring tech policy professionals should strive towards.

Emmy Ly

(This article was written by Emmy Ly, Fall 2025 communications intern.)

Emmy Ly served as the Fall 2025 Communications Intern at TechCongress, where she managed public-facing communications and supported the organization’s mission to recruit and strengthen technical capacity in Congress. She brings a background in cybersecurity engineering, strategic communications, and technology policy, with a growing focus on AI, cyber defense, and digital security and privacy. Emmy previously held positions across the executive branch and in Fortune 500 companies, and she is active in leadership roles within several national security and technology-driven organizations. She is a recent graduate of the George Washington University, where she earned her B.S. in Information Systems.

Find Emmy on LinkedIn here.